- Home

- Matthew Seaver

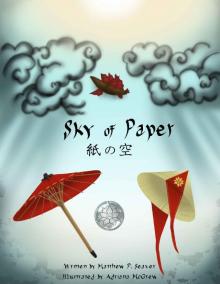

Sky of Paper: An Asian Steam-Driven Fantasy Tale Page 2

Sky of Paper: An Asian Steam-Driven Fantasy Tale Read online

Page 2

When I came home, I hurried to the kitchen and washed my face over the water basin, then took a wet cloth and wiped away the dirt from my arms and neck, knowing that if my sister discovered any evidence of what had happened, she would be furious. Though I wiped most of the blood away, I could still feel the sores around my eyes, and cheeks. My body twitched and my eyes watered against the chilly air. I hurried to my room to change into clean clothes, but froze when I saw my sister from the doorway of my mother‘s bedroom. She was home early that day. Thankfully, her back was to me as she knelt in front of mother‘s shrine in silent prayer, which was nothing more than a sheet of paper with the characters of my mother's name written upon it, hanging against the wall. She had placed some burning incense sticks in a bamboo cup beneath it.

I had every opportunity to slip past her and yet, it was a sudden feeling of guilt that beckoned me to remain in that doorway. Rarely had I ever seen her in solemn, spiritual reflection. I had always known her to be a strong, determined person, and yet, this was another part of her I always suspected she kept hidden away. I didn’t know why she was so secretive about it. I could only guess that she was probably afraid that I would think of her as a more frantic, hopeless person for praying to our mother, maybe even think that I would mistaken her prayer as some manner of shameful pleading or groveling. I waited until she was done. She was quick to suppress her shock when she opened her eyes and found that I was there. Then, as if pretending that she were greeting me at the front door she said, " did you bring the wood?"

I didn’t answer. Then the shock she suppressed an instant before, returned when she noticed the blood on my clothes and the purple marks near my eyes. She gasped and darted towards me, holding my face in her hands. She asked me what had happened and who had done this to me. I did nothing to hide it. I told her I was in a fight.

Sister's hands were always stained with dyes from the factory. Sometimes, when she came home from work, her face also had spots of unnatural color. But as she inspected mine, she seemed sad, as if the colors on my face were an unworthy reflection of her. . . of the ones she had on hers. She slapped me hard. Before I had a chance to react, she slapped me again and again, until I could no longer look at her. I thought she was angry, but all I heard was sorrow in her tone as she spoke.

"Promise me you won't disgrace us ever again."

I looked at the ground, bit my lip and clenched my fists until they shook. I tried to say, ‘I promise,’ but I couldn’t find the strength to mouth the words. Instead, I nodded slowly. She then wrapped her arms around my shoulders and hugged me as hard she could. All at once, my pride disappeared, leaving me with the humility to say, "I'm sorry.

Little Dragon Boy, was what he called me after that day. For weeks, I would travel to the mill to fetch wood, only to find that same young man in the brown overalls waiting for me. My sister had told me that his father owned the mill and that he spent most of his days working there, watching over his father's business. Though I never noticed his presence before, I was now left with the dread of seeing his face whenever I went there. At first, he used the name as an insult, saying childish things like, "look at the scared little dragon boy", "watch out, or you might be eaten by one of the sky monsters little dragon boy" or, "poor little dragon boy, all he can do is throw pebbles."

I learned to ignore his words, growing stronger each time I managed to keep from showing him my anger as I simply took the wood from the pile, paid him and bowed respectfully in silence.

Soon, he started noticing my calm, reserved demeanor. Aside from that violent day we traded blows, he never saw me cry or show any anger, especially when he insulted me with his "little dragon boy" comments. One day, he stopped speaking in my presence. We simply nodded to each other as we exchanged wood for money. Perhaps he realized how much I had grown since then, or perhaps he simply ran out of insults, but three months later, before I left with another wood bundle in my arms, he looked at me with the same stone-like expression I gave him and said without a single hint of animosity, "take care, little dragon."

Later, I learned that his father had died from a disease a week earlier -reportedly the same one that had ended the life of my mother- and that he’d become the new owner of the mill. He had to accept that it was his time to grow up, to let go of senseless grudges that would only get in the way of his duties. It was time for him to become an adult.

From that moment on, he simply called me little dragon, a name that I felt was more like an honorary title, than a nickname. I decided it was time to put my own animosity towards him behind me, and maybe even offer him a small measure of respect.

The Summer festival was one of the few holidays the village of Rune honored. Unless you had a job in one of the festival booths or in the town committee, no one was allowed to work that day. This was the one day of the year where I felt truly excited, the day I always looked forward to. Everything about the festival was a celebration of life, prosperity and good fortune for the coming year. It was also one of the few times I was able to see my sister stop acting like an adult and be the older sister she would’ve been if our mother was still alive.

The celebration didn’t start until the lanterns were lit in the evening and the music from side-walk musicians began to play. It was customary to wear colorful, decorative robes during the festival, but no one could afford such things, so instead, we wore our day clothes. My sister however, always wore her make-up and did her hair in two separate buns, both tied off with red ribbons. In the festival of my thirteenth year, she almost looked like an unblemished teenager again, except for the dye stains on her callused hands and one small stain on her cheek. To me, she was the perfect symbol to our town's spirit. Though she worked hard every day, she still found it important to celebrate and enjoy life regardless of how grim things had become.

Though the town couldn’t afford much, we still had enough to celebrate and enough to be happy. Food was not plentiful, but the booths still cooked small portions of fried squid, steaming dumplings and fresh pork buns. The town leader always made sure that every possible thing that made a festival, a festival, was preserved in some way, even at the sacrifice to some quality or quantity. I was glad, because the atmosphere was always enchanting and vibrant enough to leave a lasting smile upon my lips. The murmur of bustling crowds and laughing children, the smells of food, the shouts of game booth attendants enticing people to play their cheap games for even cheaper prizes, even the sparse fireworks used to scare away evil spirits, made me swell with laughter, and for a time, even hope.

"The wood mill owner thinks I'm a man now."

She was close behind, with her arms resting on my shoulders as we went down the village‘s brightly lit main road. It was decorated and crowded on both sides by booths. And on the far end, it even had a performing stage. She laughed, squeezing shoulders. "My brother is a man now? This is the first I've heard of it."

"It's true Sister. He also gave me a nickname. Whenever we meet, he calls me little dragon."

"If he calls you little, then how can you be a man?" She pinched my cheek, and I jerked my head away, annoyed.

"But, he calls me little dragon. Anyone who has 'dragon' in their nickname has to be a man. Maybe he meant I was a little man, not quite old enough to be a great man."

We stopped at a booth, where she bought me some skewered fried squid. When she handed it to me, she smiled, like a mother about to reveal a glorious secret. "Terr, there’s no such thing as a little man, or even a great man. You’re either a man or you’re not. It’s just like marriage. You’re not partly married or mostly married. You’re either a single person or you‘re bound to the one you love. It looks like your school making you think too much about stuff that shouldn‘t matter. Some things are much simpler than you think."

I wondered if this time she was the naïve one. In my elderly years, I’d come to understand that nothing is ever simple. When a man says one thing, he may mean another, when we do something that we deem as noble, we

may, in fact, be doing evil. It’s just as if we took a brush and stroked a character on a piece of paper. Is it art, or is it just a word? I later learned, that it’s both; that words and art are one and the same, just as I look back to that festival so many years ago and understand now that I was both a child and a man. Certainly, that’s what he must have meant when he called me little dragon.

Of course, still being so young, and understanding nothing of the world, I easily took my sister’s words to be the truth. I bit down on the fried squid and nodded, grudgingly accepting her wisdom. She then took my hand and for the next few hours we ran from booth to booth, playing games and watching performers entertain the crowds. I saw a man give a wondrous juggling act with sticks of fire, and before he finished, I found myself being dragged towards a game booth, and just as we finished the game, she eagerly pulled me to the next show or booth. It wasn’t long before I became annoyed, but she continued to smile or laugh showing no empathy for the frown on my face.

"Sister, wait!"

"There's no time little brother. I want to do everything twice before the festival is over."

It was an impossible task considering how large the festival was and how little time there was left to celebrate. Still, she was ambitious, trying hard to fit so much in one, single night. I was certain that she wanted to make up for all the days she was cooped up at the factory.

There was one particular event, however, one that the both of us always took the time to see. It was a performance so unique, so rare, that the entire village gave pause to its festivities in order to witness it.

It was the dance of the chienkuu ko.

They were known as the children of the sky, or chienkuu ko in the old language. Many of them not much older than I, they possessed certain talents thought to be so amazing, that the Emperor deemed them keepers of the traditions and sacred culture of Rui Nan. At the time, I had only known them as honored performers, for it seemed they only appeared in our village, but just once a year to dance for our festival, then, all-too quickly return to the mysterious place they came from. Since they were direct representatives of our country’s pride and demanded the respect of everyone's attention, the village leader always made sure they performed at the end of the festival, closing all the booths and assembling everyone at the massive, wooden stage, built just for them at the front of the temple.

Complete silence. Thousands of eyes were upon the stage, where eight children, four boys and four girls, slowly and ritualistically stepped to their places. The elaborately decorated girls all wore red silk robes with patterns of chrysanthemums, the imperial symbol, woven into the fabric with gold-colored thread. Their hair was neatly tied in single, large buns at the back of their heads, with gold and jade flower decorations dotting the crest of their hair. This was, but the single time of year of my young life where I had a chance to see people wearing actual kimonos. And it seemed strange to me that anyone could wear something that looked so intricate and fragile.

I was at the back of the crowd and could barely make out the girls’ faces, as they were mostly hidden behind a vibrant mask of brightly colored make-up. As they kneeled down at the back of the stage, it seemed to me they weren't children at all, but instead, dolls; beautiful and graceful. The boys wore men's kimono's made of heavy blue silk. They also wore kimono trousers, or Hakamas, which were long, pleaded skirts that reached down to their ankles. On their chest was woven a single gold imperial chrysanthemum. Their hair was also tied off into single buns, wrapped with thick, black thread. Their faces seemed rigid and focused, with little trace of emotion as they proceeded to the front of the stage like monks in the middle of prayer, standing side-by-side while facing the crowd.

Without any introduction, the show began with the girls playing drums of all shapes and sizes with rhythmic beats both deep and primal, and light and spirited. The boys then danced with swift arm and leg movements, as if fighting some invisible enemy. All four were in sync with body and limbs moving as one, with motions so fast and deliberate, the full lengths of their arms seemed to disappear in blurs, holding one stance for just a brief moment, then snapping to another. Most of the movements were with the upper body, with torsos and arms. They were like trees, with legs rooted to the ground immediately after they made a change in their stances. Their torsos and arms twitched and swung like snapping branches. My sister told me that this was the Spirit Tree dance; a dance that honored the spirits of the forest, which made the plants grow and the crops plentiful.

I’d learned in my classes that a few hundred years ago, dances such as these were an important part of our culture. There was a dance for every way of life, from endowing men with courage before the day of battle, to bringing good fortune to a couple on their day of marriage. For something so old, it seemed odd to me that I’d only seen children perform the traditions of the old ways. Watching them dance year after year, I slowly came to understand that the chienkuu ko were more than just performers, they were living visions of who we once were. The drums crescendoed and their thudding echoes grew until I felt the ground shake beneath me. Then suddenly, the drumming stopped and all eight of the children froze in their stances.

As the crowd cheered, the girls moved to the front of the stage in preparation for their part of the performance and the boys moved to the back, kneeling down to pick up stringed instruments. Some were pipas or guzhengs, which were plucked, others were erhus, which were used with the bow. These instruments were not native to Rui Nan, but instead, came from the Eastern Kingdom in Kin Ju, a large nation that lay across the ocean, who's culture seemed so similar to ours, that the only major difference between us were our languages.

Once the crowd was silent, the music began. This time, the sounds were soft and soothing. The female performers spun red and gold folding fans in their hands, waving them slowly in the air as they moved in circular motions, shuffling gracefully across the stage from one spot to the other. They moved like butterflies, following the steady flow of an invisible breeze and spinning and moving side ways like leaves in fall. Like the one before it, this dance celebrated yet another spirit. Called the Air Spirit dance, it honored the dreams and passions that inspires us all to live without regret. The gentle movements of their bodies represented one of two choices we must all ultimately make. Would we be like helpless leaves, letting the wind take us wherever it wishes, or sprout wings and choose our own direction?

I proudly explained to my sister, the meanings of the dances I‘d learned in school. She gave me a prideful look, as if she already knew.

When she replied, keeping her eyes squarely on the stage. "A dance is just a dance little brother, no matter how beautiful or meaningful it might seem. You should learn to accept things as they are, not as what they might be."

Though it seemed she had no interest in the spiritual meaning of the performance, she was still enchanted by the music, the motions and the beauty of the grand event before her. Her gaze was just as intent as mine. We were peering into another world through a window, it seemed, where people dressed and acted as perfectly as the eight young performers before us.

We were such humble people. We had no jewels, no silk robes, nor did we see anything about ourselves that we considered special. We did common things in the eyes of the Emperor, yet every year, these children, his most valued works of art, came to perform. Whether it was his way of thanking us for all our hard work, or reminding us of his benevolence, I was most grateful for a chance to glimpse at the possibilities that lay beyond our village.

Decades later, I can recall a number of times when my children and grand children have asked me, why they were called chienkuu ko, or children of the sky. Secretly, I tell them that the answer is simple: with their very will, they can change the motions of the sky. The oldest of my children often laugh and shrug it off as the ramblings of an old man. But amongst my younger ones, my answer sometimes manages to intrigue them and I tell them what was meant by my words by describing the final act of the summer fest

ival performance.

After the Air Spirit dance had concluded, the four girls once again went to the back of the stage, then sat down and folded their hands neatly on their laps. They sat completely still, gazing off into the distance, as if pretending to be Buddhist statues. All four of the boys went to the front, standing patiently as monks in red robes placed four large stones, each carved into the shape of fish at their feet. Several other monks, far behind the stage, then began beating a rhythm from their drums. For a moment, everyone on the stage was completely still, as the eight children gathered their focus.

I watched with such eagerness, that I was afraid to blink. Glancing at my sister, I saw that her mouth was open like a fish, entranced by a piece of bait. For several minutes, they did nothing while the drum beats remained steady, simmering the audience’s anticipation. Then, I felt the startled grasp her hand as she took my arm. The four stone fish began to rise up into the air as the male performers made slow, vertical hand motions. The objects levitated slowly to the height of their shoulders, bobbing and swaying like a leaf on a wavy pond. It was at this point that a few doubtful words were murmured throughout the audience. Some had said they found the wires or a dangling bit of string, but like every year before, I was still unable to find a single trace of evidence proving their claims. Still, I had lingering thoughts, wondering if it was indeed a trick or some sort of illusion. My sister, who was usually a down-to-earth sort of person, thought otherwise. Like almost everyone else in the village, she believed it was real, or rather, maybe she wanted to believe it was real.

With great, big, sweeping hand gestures, the fish-shaped stones darted from one direction to the other, imitating the motions of a school of sea creatures. They dove to the performer's feet, then climbed to the tops of their heads, all the while, following graceful, arm and body movements. It was like watching a parent, teaching their child to dance. A performer would step and move a certain way, and the stone fish would follow in their wake, imitating their motions in a similar fashion. Wild cheers were given as the four fish flew from the stage to the very center of the crowd, just above our heads. They circled in wide arches, then small ones, as if they were curious of the gazing people below them. What was once idle stone, had all-at-once, become as alive as any animal.

Sky of Paper: An Asian Steam-Driven Fantasy Tale

Sky of Paper: An Asian Steam-Driven Fantasy Tale